Showing posts with label WTC. Show all posts

Showing posts with label WTC. Show all posts

Saturday, September 22, 2012

Thunderheads

Let’s talk about the weather.

The summer in New York seemed different this year, powerful in an old way. Most days the air sat thick and hot on us, the sky a lens held above us by a boy who hasn’t yet begun worrying about himself as cause. And the storms. We look out from pretty high windows now, and we have a clean view north and west over and up the Hudson, which is where our weather comes from. Over and over we watched the ecstasy of meteorologists on the Weather Channel appreciating red running across the radar, the lines thick like wire once twisted up that someone gave up on trying to pull straight again. We watched the radar-red fronts menace in, watched the sky turn the color of a bruise. The heat made for huge thunderheads, easily ten times taller than anything in this city of tall buildings, including those two we remember being taller than they were. Many times we saw the clouds come down below the building tops and pretend to be ghosts chasing each other out to the ocean. It was all enough to make a person think up gods just to give them what they want.

I like watching weather from closer up, sure, but I still find myself missing the Western Kansas sky, the one that comes all the way down to you. I miss the weather talk, too. Most conversations in the Midwest still begin and end with the forecast, even though few conversationalists these days are farmers whose livelihoods hinge on the character of the climate. To someone passing through, such talk probably comes across as casual and irrelevant, an avoidance of communication instead of a species of it. But it’s not hard to account for its persistence and prevalence: All that sky makes for storms that seem bigger than the planet. Fronts can be spotted easily 50 miles off, and though they always move faster than they look (as giant things do), they leave a fair amount of time for theory and speculation. And it’s more than theory. Kansans have learned to know the quickest ways to their basements. When they mention rain at the post office and the restaurant, it’s a form of the oldest and most basic social cement, like prairie dogs passing around a warning about a hawk.

But now fall. In New York the summer storms have gone in favor of darkening mornings that spin to clear sky blue. The poets got it wrong: Fall makes a poor stand-in for the onset of the end of something. To my mind, it’s hard to think clearly in the summer — to think at all really — but when the air cools, thoughts and what they’re about can become further apart. We locate our sleeves and begin wondering about our jackets; doubts about gods reroot. September brings back an interest in the inside of things.

What’s your weather like?

Friday, January 20, 2012

Memorial

We go up Liberty Street (this choice perhaps deliberate, something America would totally do) to Greenwich, through sluices of concrete blocks to slow movement, to where a surprisingly small number of people point cameras at the construction. The entrance to the 9/11 memorial is laid out to process large crowds, but it’s cold and just after the holidays, and once we present our passes we’re directed past a nearly block-long zig and zag of ropes instead of through it. Everyone and everything tells us to KEEP PASSES OUT, which we do, and they are repeatedly checked. We follow the arrows down a tunnel made from white concrete barricades topped with blue-netted fence to a glass building. A young guard dual wielding hand-held lasers scans our passes. The building turns out to be an airport-style security checkpoint, so we squish our hats and puffy coats into the bins on top of our cameras and phones. We don’t have to remove our shoes, which is good because mine happen to be complicated. The detectors don’t find us or our stuff suspicious (no one really seems to be watching that closely anyway), and we spend an equal amount of time on the other side gearing back up. To exit we must show our passes, which we do, and then we follow more barricades and arrows pointing and making the path up to Ground Zero, this time right along the West Side Highway with New York in a hurry. A guard at the entrance to the memorial proper asks for our passes and, once satisfied that we belong there, waves us into the site.

Most of the area is still a promise, an idea slowly unfolding. The museum, looking like a chipped box sinking on one end, isn’t open yet, and cupping our hands on the glass reveals a deep and broad space with a long way to go. The new swamp oaks stand in place, but they have given up for the season. We all take pictures — The Boy already has his mother’s eye — and the wind searches for our bones through our clothes. I loved to look straight up at a twin tower from its base, the way eyes work bending the top back toward me. You would swear they were built on a dare. But the new main building, now thankfully referred to simply as 1 World Trade Center, doesn’t have a precarious thing about it. Its heavy base leads the eye to compress it, to hold it down. Perhaps when I can stand close in the finished plaza I will see things differently.

The waterfalls, however, are complete. I remember the fraught memorial design competition, and of the finalists, this one was not my choice.* I thought the emphasis on the tower footprints was too literal and heavy-handed, dwelling on the holes blown in lives and not the healing. Still, realized, they do make a powerful impression. Each is a sunk black box with water falling geometrically for about forty feet then pooling into a smaller square in the center. Lights run around the base edge of the pool, and the water coming down carries the light up into it, multiplying it in interesting ways. The names of the dead, so many names, have been cut into the black metal that frames the waterfalls. I pull out my phone and use the memorial’s web app to look up my wife’s law-school roommate. We locate his name near a corner of the north waterfall, and as the evening comes on we can see it glow from below. I have read that the sound of the water was designed to muffle the city and to promote contemplation. But when I close my eyes, the evenness of the roar conjures up airliners in flight — cruising, though, not accelerating, not approaching on a violent angle. Still, I assume this was not intended.

And contemplation does not bring comfort. Memorials can provide places to offload grief, but so much remains unfinished even now, ten years out from 9/11. My thoughts about the attacks, ruminated into neater shapes over the years, have begun to show their original ragged edges. The war in Afghanistan, becoming medieval in its duration and destruction, is somehow older than Q and The Boy. I remain mostly proud of my city, less so of my country that became a wildly flung fist. I don’t know what to do or to think about any of it.

After only a little while, the cold wins, and we go back through the barricades and out into New York to eat. Always go back to the body. We order burgers and fries just a few blocks over at a place we’ve been wanting to try, and we crack peanuts from their shells while we wait for the food to arrive. Construction and change are everywhere; this neighborhood can’t become itself fast enough.

Remember, but don’t let memories get in the way. Write down the names where they can be touched and traced. Yes, a pool, too, but a small one with its own shape. And leave the surface still so that it can borrow the blue of the sky, can reflect the rising buildings and the office workers on their lunch. Make the place easy to enter and cross. Invite the whole loud, living city here, on foot and by train. Remember why we dig graves so deep and cover them with earth.

Most of all, make people look up.

_________________________

*I am, of course, precisely nobody.

Saturday, September 11, 2010

Incantations

September days in New York recapitulate a year of seasons: mornings cool and dark giving way to afternoons bright and hot. Today will be as clear and blue and usual as that day—or maybe more so, it's hard to trust the memory now that so many have handled it.

Burn the buildings, burn the books. Read out the names again.

Today we celebrate our bodies without really meaning to, Q at gymnastics and The Boy at soccer. My lovely wife and Q make their way uptown to the gym on scooters; The Boy and I kick around our nerves out in the park until game time. Then swimming in the afternoon around the time of the protests, new this year. The mind always trailing the body, getting in its way. Ground Zero lies just a block off, and I see the new building finally rising. Rumor has it they found an old ship at the site—what you find when you dig.

This morning my daughter asks me how we're made.* It's not the awkward and inevitable question of conception. No, she's taken by the larger mystery of how we as things that see, that hear, that think have come to be at all. This is my kind of question, and we begin the long story that goes back before all tellers, the one that has the shape of magic.

But however great the incantations, we can't seem to stop the stories of our unmaking.

________________________________

*Seriously. Not kidding.

9/11 Archive:

Burn the buildings, burn the books. Read out the names again.

Today we celebrate our bodies without really meaning to, Q at gymnastics and The Boy at soccer. My lovely wife and Q make their way uptown to the gym on scooters; The Boy and I kick around our nerves out in the park until game time. Then swimming in the afternoon around the time of the protests, new this year. The mind always trailing the body, getting in its way. Ground Zero lies just a block off, and I see the new building finally rising. Rumor has it they found an old ship at the site—what you find when you dig.

This morning my daughter asks me how we're made.* It's not the awkward and inevitable question of conception. No, she's taken by the larger mystery of how we as things that see, that hear, that think have come to be at all. This is my kind of question, and we begin the long story that goes back before all tellers, the one that has the shape of magic.

But however great the incantations, we can't seem to stop the stories of our unmaking.

________________________________

*Seriously. Not kidding.

9/11 Archive:

- Not quite done with 9/11, I suppose (2009)

- On collision (2008)

- I want to tell them (2007)

- By accident (2006)

Monday, September 14, 2009

Not quite done with 9/11, I suppose

I suppose I'm getting better about the September 11th attacks. I no longer pay much attention to low-banking planes overhead, and we didn't feel like braving the rain for the still-arresting Tribute in Light. I likely wasn't going to say anything about it here either; I've already turned things over in my head here, here, and here.

It's not that we've forgotten. We still think about the kids of the dead, the ones we knew and the ones we didn't. We still live in one big construction site that, from the looks of it, will always be one. We still see the parades — shorter every year — of fire trucks and hallowed slag. The memories are just more distant now, and with Q and The Boy growing right before our eyes, it's hard to look at much else.

But then Facebook (of all things) kicked me back. Last Friday morning, among all the quiz results and posted photos, I saw a status update from a childhood friend of mine that he was in Kuwait waiting to deploy to Iraq. We haven't been all that close for a while now, but we knew each other for many of the years that a lot of books call formative. He's an Army physician with seminary and philosophy training as well, and in the picture he stands in fatigues in a sun-blasted background, huge buses over his shoulder perhaps ready to take him somewhere that I can't quite fathom.

Yes, the wars are still going on, particularly the one that had nothing to do with the hole in this city. May it all end soon and safely, for him and for others. May there be fewer holes in lives.

It's not that we've forgotten. We still think about the kids of the dead, the ones we knew and the ones we didn't. We still live in one big construction site that, from the looks of it, will always be one. We still see the parades — shorter every year — of fire trucks and hallowed slag. The memories are just more distant now, and with Q and The Boy growing right before our eyes, it's hard to look at much else.

But then Facebook (of all things) kicked me back. Last Friday morning, among all the quiz results and posted photos, I saw a status update from a childhood friend of mine that he was in Kuwait waiting to deploy to Iraq. We haven't been all that close for a while now, but we knew each other for many of the years that a lot of books call formative. He's an Army physician with seminary and philosophy training as well, and in the picture he stands in fatigues in a sun-blasted background, huge buses over his shoulder perhaps ready to take him somewhere that I can't quite fathom.

Yes, the wars are still going on, particularly the one that had nothing to do with the hole in this city. May it all end soon and safely, for him and for others. May there be fewer holes in lives.

Thursday, September 11, 2008

On collision

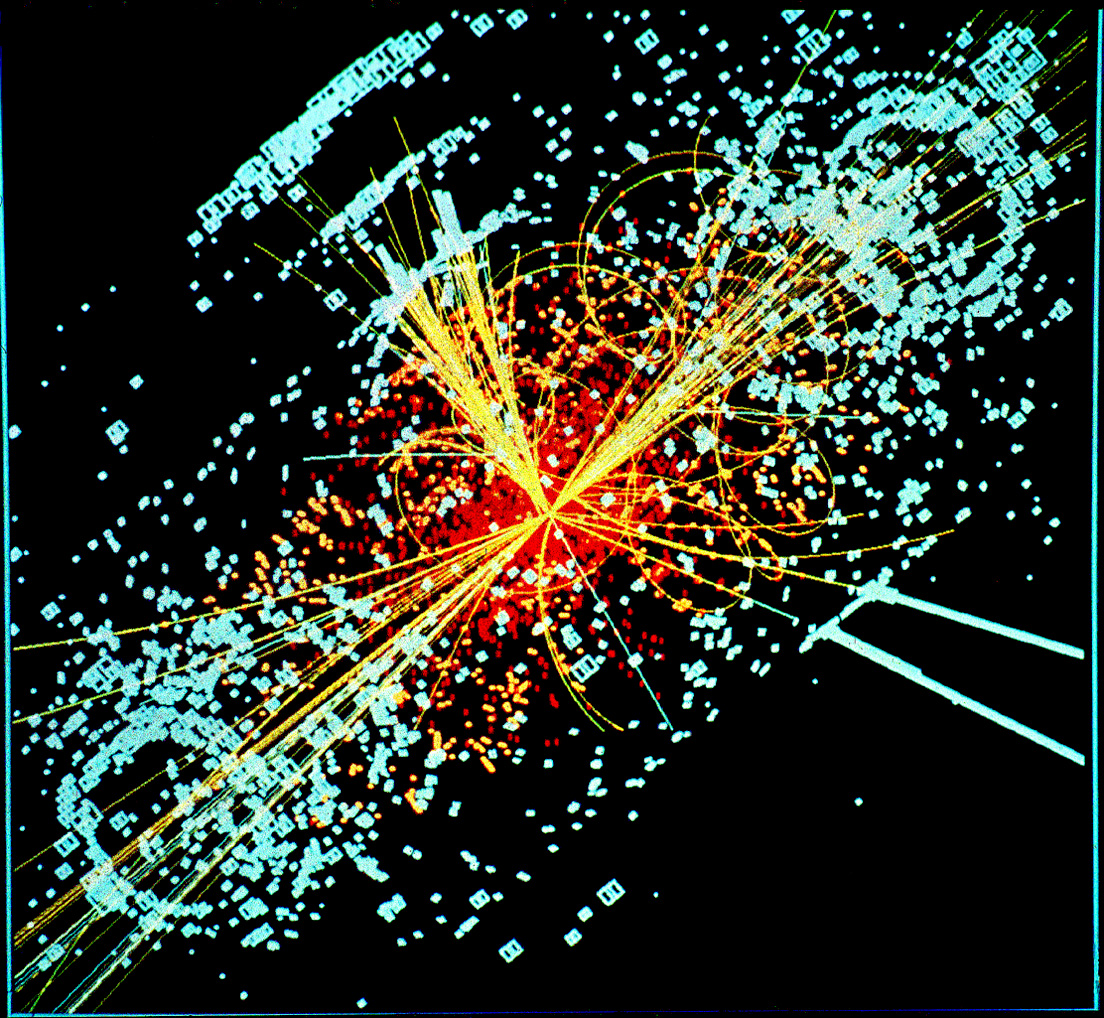

The first beams cycled through the Large Hadron Collider yesterday deep under Switzerland and France. It's the world's largest particle accelerator, designed to hurl bundles of protons into each other at nearly the speed of light so as to break them open and reveal the seams of all things. The collisions themselves don't begin until October, and people have joked (a little uneasily, I think) that the scientists at CERN might produce black holes, though small, still sufficiently strong to swallow the earth.

Collisions do reveal. There is an energy, mysterious and calamitous, that holds the hardest bodies together, but we have learned that speed and thought can break loose almost anything, can open a hole. Some things are here, then not — the particles, no longer parts, return to being elementary. We can't seem to stop studying them.

Bodies obey laws. Accelerate the heavy jets and they will knock the rigid structures down into a hole that can't be built over with concrete or flags. Discover the weakness, make pieces, study the streaks in the clouds. What's left will ratify gravity.

Mass. Motion. Force. Sometimes I think we can know too much.

(I keep telling myself I will stop writing about September 11 in one way or another. Perhaps next year.)

Tuesday, September 11, 2007

I want to tell them

I come into the World Trade Center PATH station, as I do every day now on my way home, and from the train these days the rows of rebar and steel beams make the place look like a grave site, a ditch of bones. Then up the long escalator and the stairs to Church Street and a mob of police, protesters, tourists, and people like me walking fast to get home. Signs about war. National Guard in green fatigues with serious guns. People with camcorders and mics recording in languages I don't speak. The day puts me in my head. I want to tell them what happened here on this day before they were born, tell them why it happened and that it's okay to feel covered by thick sadness, to care for those we don't know. I want them to be small, to fit in my hand, so that I can shield them from falling things. I want them never to smell acres of burning plastic, to run from dust. I want them never to wonder where someone is while really knowing. I want to tell them that wisdom wins in the end and want to believe it. I want to tell them that war ends (and want to believe it). The fountains are on in front of 7 World Trade Center; traffic knots. So glossy and glass, 7 World Trade becomes the sky when you look up into it. (Intentional?) I want to tell them that bodies are soft, held together by something ancient and loose. Up the elevator in the skyscraper where I live; down the long hall. I want to tell them.

Inside they are painting, and it's quiet; they are into their work.

I want to tell them but don't want them to know.

Monday, September 11, 2006

By accident

Early on in Walden, Henry David Thoreau writes:

It's the fifth anniversary of the attacks on the World Trade Center towers today, and it's impossible not to think and rethink about that day. When I do, the Thoreau passage keeps creeping back into my head, usually from the side. My wife and I have lived in New York for about twelve years now (and, for what it's worth, it sometimes still seems as though our house is like Thoreau's--merely a defense against the rain). We lived in Greenwich Village in 2001, a historic neighborhood about a mile or so north of what's now called Ground Zero. From a corner of Sixth Avenue, I watched a tower collapse into itself while my wife glided to work underground as usual on the 2 subway train. She had to walk home with thousands of others not long after arriving in Midtown. The entire landscape of the city had become a target; every set of stairs had become a racetrack.

We're still here, five years later, now living a few blocks from where the towers stood and from where construction has finally begun to make something of that place. I think about what happened there often enough, I suppose--sometimes of my wife's law school roommate who died and his young son who can only remember him, sometimes of those who chose to leap from the broken windows 80 stories up instead of waiting for what was coming for them, whatever it was. Sometimes when I'm pushing Q and The Boy on the swings outside our building, I catch myself being suspicious of an airliner that seems to hang, just for a moment longer than I think it should, over the Hudson on approach to LaGuardia Airport.

As for bigger changes, I don't know. We have a discussion with all our babysitters as to what to do in case of an attack, which, thankfully, my brother and his wife who live in the Midwest don't have to have with those who watch their boys. I do worry (probably less than I should) whether we're breathing little bits of the towers even now and what that means for the kids. I don't know. If we had Q and The Boy five years ago, we may very well have left the city like several of our friends. But in those days following the attacks, as we walked by the walls covered with posters for the missing and the quiet lines of people waiting to give blood, we decided not to let go of New York. Not yet.

We were not alone. Perhaps ironically, our neighborhood--five years ago nothing more than broken windows and debris under otherworldly dust--is thriving. It's one of the greenest areas in the city, and one of the fastest growing. We've seen at least five new apartment buildings rise up and sell out since moving down here. A public library will soon be built across the street from us (sharing space with luxury condos, of course), as will a high-end bakery and coffee shop. Here comes the neighborhood, as we like to say.

We were not alone. Perhaps ironically, our neighborhood--five years ago nothing more than broken windows and debris under otherworldly dust--is thriving. It's one of the greenest areas in the city, and one of the fastest growing. We've seen at least five new apartment buildings rise up and sell out since moving down here. A public library will soon be built across the street from us (sharing space with luxury condos, of course), as will a high-end bakery and coffee shop. Here comes the neighborhood, as we like to say.

More generally, the date 9/11 has become a name for something that was inevitable--or at least a shorthand for the moment when everything suddenly became profoundly different. Some even believe that those who planned the attacks chose that particular day because it's the number we dial in emergencies. (That's unlikely, though, given that we're one of the few countries that write our dates with the month first.) To put it a little differently, I can understand why someone might think that day was inevitable. Fated.

But it's worth pausing for a moment--perhaps on this day more than another--to think about what it means for something to be accidental or to happen by accident. Philosophers like to make the distinction between something's being accidental or extrinsic and something's being essential or intrinsic. Intrinsic features determine what a thing is. In this sense, 9/11 is an accidental event, one arising from a galaxy of factors, internal and external, American and otherwise. It's not of our American essence, I think, that we should be attacked. I'd like to think that a single day, however horrific, cannot determine us.

We have a life here, and in many ways a good one. We see the Statue of Liberty each time we fall out into the parks close by; we fit pretty neatly in this amazingly international city that statue overlooks. Perhaps I naively comfort myself by thinking, though so many made so many choices that blue-skied September morning, any day and no day could be just like that one.

"When first I took up my abode in the woods, that is, began to spend my nights as well as days there, which, by accident, was on Independence Day, or the Fourth of July, 1845, my house was not finished for winter, but was merely a defence against the rain, without plastering or chimney, the walls being of rough, weather-stained boards, with wide chinks, which made it cool at night."The striking thing about this passage is that Thoreau essentially declares his independence from America on the day that America celebrates its own independence, and that he notes this was "by accident." He didn't, in other words, make the date of his leaving anything particularly auspiscious, and in doing so encourages his reader to think that our country's own independence was, in an important sense, equally accidental.

It's the fifth anniversary of the attacks on the World Trade Center towers today, and it's impossible not to think and rethink about that day. When I do, the Thoreau passage keeps creeping back into my head, usually from the side. My wife and I have lived in New York for about twelve years now (and, for what it's worth, it sometimes still seems as though our house is like Thoreau's--merely a defense against the rain). We lived in Greenwich Village in 2001, a historic neighborhood about a mile or so north of what's now called Ground Zero. From a corner of Sixth Avenue, I watched a tower collapse into itself while my wife glided to work underground as usual on the 2 subway train. She had to walk home with thousands of others not long after arriving in Midtown. The entire landscape of the city had become a target; every set of stairs had become a racetrack.

We're still here, five years later, now living a few blocks from where the towers stood and from where construction has finally begun to make something of that place. I think about what happened there often enough, I suppose--sometimes of my wife's law school roommate who died and his young son who can only remember him, sometimes of those who chose to leap from the broken windows 80 stories up instead of waiting for what was coming for them, whatever it was. Sometimes when I'm pushing Q and The Boy on the swings outside our building, I catch myself being suspicious of an airliner that seems to hang, just for a moment longer than I think it should, over the Hudson on approach to LaGuardia Airport.

As for bigger changes, I don't know. We have a discussion with all our babysitters as to what to do in case of an attack, which, thankfully, my brother and his wife who live in the Midwest don't have to have with those who watch their boys. I do worry (probably less than I should) whether we're breathing little bits of the towers even now and what that means for the kids. I don't know. If we had Q and The Boy five years ago, we may very well have left the city like several of our friends. But in those days following the attacks, as we walked by the walls covered with posters for the missing and the quiet lines of people waiting to give blood, we decided not to let go of New York. Not yet.

We were not alone. Perhaps ironically, our neighborhood--five years ago nothing more than broken windows and debris under otherworldly dust--is thriving. It's one of the greenest areas in the city, and one of the fastest growing. We've seen at least five new apartment buildings rise up and sell out since moving down here. A public library will soon be built across the street from us (sharing space with luxury condos, of course), as will a high-end bakery and coffee shop. Here comes the neighborhood, as we like to say.

We were not alone. Perhaps ironically, our neighborhood--five years ago nothing more than broken windows and debris under otherworldly dust--is thriving. It's one of the greenest areas in the city, and one of the fastest growing. We've seen at least five new apartment buildings rise up and sell out since moving down here. A public library will soon be built across the street from us (sharing space with luxury condos, of course), as will a high-end bakery and coffee shop. Here comes the neighborhood, as we like to say.More generally, the date 9/11 has become a name for something that was inevitable--or at least a shorthand for the moment when everything suddenly became profoundly different. Some even believe that those who planned the attacks chose that particular day because it's the number we dial in emergencies. (That's unlikely, though, given that we're one of the few countries that write our dates with the month first.) To put it a little differently, I can understand why someone might think that day was inevitable. Fated.

But it's worth pausing for a moment--perhaps on this day more than another--to think about what it means for something to be accidental or to happen by accident. Philosophers like to make the distinction between something's being accidental or extrinsic and something's being essential or intrinsic. Intrinsic features determine what a thing is. In this sense, 9/11 is an accidental event, one arising from a galaxy of factors, internal and external, American and otherwise. It's not of our American essence, I think, that we should be attacked. I'd like to think that a single day, however horrific, cannot determine us.

We have a life here, and in many ways a good one. We see the Statue of Liberty each time we fall out into the parks close by; we fit pretty neatly in this amazingly international city that statue overlooks. Perhaps I naively comfort myself by thinking, though so many made so many choices that blue-skied September morning, any day and no day could be just like that one.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)