It probably started the Halloween my parents made my brother his Ace Frehley costume. I can't pinpoint the year precisely, but it had to be the late 70's, when his then-favorite band KISS rose to prominence, penetrating even our remote Midwest with their makeup and blood-spitting and smoking guitars. The band was more or less a troupe of trick-or-treaters from the beginning, so it's not surprising that kids would eventually show up at their neighbors' doors ready to Shout It Out Loud. I suppose it's also not surprising why my brother chose the band member he did. Paul Stanley, with his aggressively hairy chest, would have been a bold choice in those days, and, as far as I can tell, nobody really wanted to be Gene Simmons, battle-axe bass notwithstanding. Frehley (like cat-faced drummer Peter Criss) hardly ever spoke, but he had a spaceman ("Space Ace") theme to his getup, which made him a prime target of boy-emulation.

My brother's Ace Frehley was, not to oversell it or anything, simply awesome. My parents glittered huge swoops of paper to make a triangle for his shoulders and huge cuffs for his wrists, and they converted his off-brand moonboots into platform shoes truly worthy of moons. Most importantly, they painted his face white with silver star-things exploding around each eye.* I'm sure he had some sort of guitar, too, probably cardboard but with actual strings, and no doubt a wig. I don't remember the actual trick-or-treating or party going or whatever it was he did while he was Ace; I only remember the making and what he looked like.

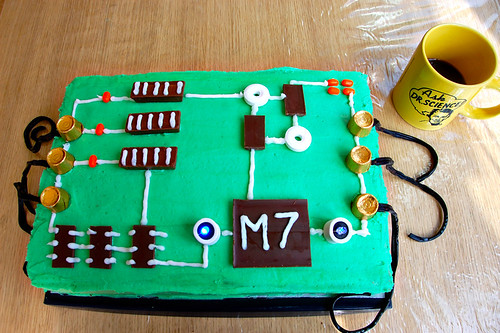

My lovely wife and I love making costumes, too. There was the first Halloween with both Q and The Boy, when they went as a Dalmatian and firefighter respectively. My wife sewed black spots to an old white onesie and black flaps for ears to an old hat. (Q supplied the smile.) For The Boy, she turned a plastic bottle, clothespin, and some red paint into a remarkably realistic fire extinguisher. Then there was the robot year, with the suit made out of boxes and brass brads and lights that really flashed. Even lately, when the kids have favored off-the-rack options like skeleton, witch, Egyptian princess, and ninja, we embellish. Though you can't really tell from the picture above, my wife made shockingly realistic shuriken out of some silver paper and ten minutes on the internet.

My lovely wife and I love making costumes, too. There was the first Halloween with both Q and The Boy, when they went as a Dalmatian and firefighter respectively. My wife sewed black spots to an old white onesie and black flaps for ears to an old hat. (Q supplied the smile.) For The Boy, she turned a plastic bottle, clothespin, and some red paint into a remarkably realistic fire extinguisher. Then there was the robot year, with the suit made out of boxes and brass brads and lights that really flashed. Even lately, when the kids have favored off-the-rack options like skeleton, witch, Egyptian princess, and ninja, we embellish. Though you can't really tell from the picture above, my wife made shockingly realistic shuriken out of some silver paper and ten minutes on the internet.

I'm not exactly sure why we do this, why we bother for a day of dress up, perhaps because there are too many reasons: a rare creative opportunity, dissatisfaction with store costumes, or just to make ourselves into makers of things.

It's hard to think about why we make masks without thinking a little about why we wear them. That's a bigger question, of course, one draped in a host of tropes. Myself, I've never really been that convinced by the common claim that most wear masks to hide themselves. Kids, after all, love to dress up, and they are only beginning to have something of the required sort to hide. Instead, I think it's the chance to become something else altogether — some nights, dressing as a 70's rock star is enough to be a 70's rock star.

There's an old story about the particular why of Halloween, of course. Like many of our traditions, this one seems to have been handed down (or up) by pagans** by way of Catholics, though it's all pretty nebulous. Anyway, it's believed that ghosts and ghouls arrived on the last day of the year to revisit their former homes, and steps had to be taken to scare or fool them back under. Funny, then, that we dress up our children and shove them out into the night to deal with the dead. Then again, maybe we make masks for children (and ourselves) because through them we might mix again with the dead, catching a bit of those who we can now see only in ourselves.

We have lost so many, and we don't know where they've gone.

*Like so.

**Druids!